What Did God Want from Cain?

It turns out that the real issue with Cain's offering wasn't the offering, but the internal disposition of his heart.

Introduction

In my previous post, I asserted that debates about the merits of Cain’s offering in Genesis 4 are a red herring, distracting from the narrative’s emphasis. I then offered a positive assessment of Cain’s offering. If Cain’s offering was acceptable by external metrics, what should he have done differently? What did God want from Cain? In this post, I will argue that what Cain needed to change was not the material or quality of his offering, but his internal disposition toward God. For Yahweh to look favorably on Cain’s offering, Cain needed to present an offering from a heart of love for God.

I’ll argue for my case by considering (1) the narrative function of the offerings in Genesis 4, (2) relevant statements in the Old Testament, and (3) New Testament interactions with this text. In the interest of brevity, I’ll refrain from elaborating fully on each point, offering only just enough information to support my case.

The Narrative Function of the Offerings in Genesis 4

Scholars adopt approaches to narrative analysis that are significantly more complex than the relatively basic approach I take here.1 Still, I would be surprised if a more technical narrative analysis would yield different results.

A basic approach to narrative analysis looks for a narrative structure that has “complication” (the setting and introduction of conflict) followed by a “dénouement” (the resolution of conflict).2 In Genesis 4, the brothers’ offerings functionally create the conditions for complication/conflict. They are a plot device to put Cain in a situation where he can prove himself to be the seed of the woman. Cain’s rejected offering provides the opportunity for him to rule over sin in contrast to his parents, who failed to rule over the serpent.

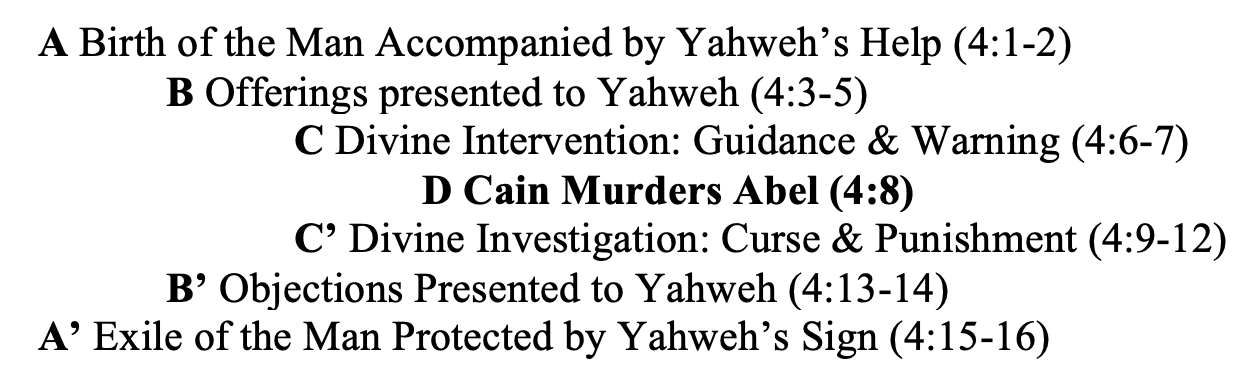

The structure of the narrative de-emphasizes the offering and instead emphasizes Cain’s act of murder and Yahweh’s interactions with Cain that frame that murder. Notice the progression:

The offerings presented to Yahweh conceal Cain’s inner person. From an external perspective, everything seems acceptable. Yahweh’s rejection of Cain and his offering provides the “complication.”

Yahweh intervenes, drawing attention away from the external to the internal by asking Cain questions about his emotional state. In other words, Yahweh knows Cain’s heart better than Cain does, and he gives Cain an opportunity to look at his heart.

Then, Cain reveals his heart through his act of (likely) premeditated murder. Cain’s act of murder provides an unsatisfying resolution of the conflict. Rather than resolution, there is escalation.

Following Yahweh’s investigation, Cain then objects to his punishment, further revealing the disposition of his heart. Then, Yahweh exercises judgment on Cain and exiles him east of Eden, bringing about the necessary resolution to the narrative.

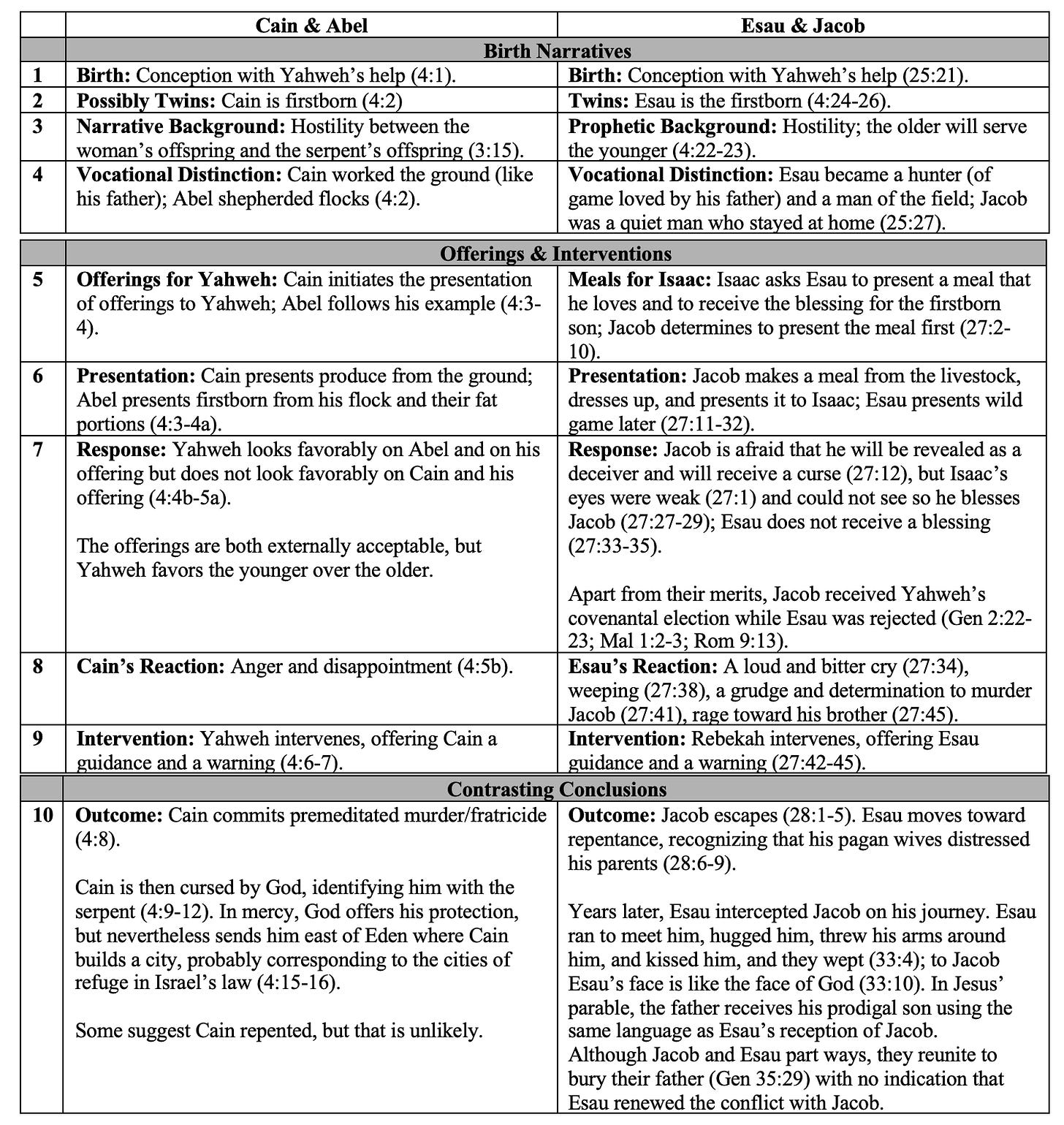

The narrative never returns to Cain’s offering. Instead, it consistently leaves the offering in the rear-view mirror. Although we might want Yahweh to give an account for his rejection of Cain’s offering, we should remember that he has the prerogative to show his favor on whomever he pleases. In the narrative analogy with Esau and Jacob, Yahweh chooses Jacob before the twins were born and before they had the opportunity to do anything to merit that favor.3 Similarly, Yahweh’s rejection of Cain has little to do with the offering itself and everything to do with Cain.

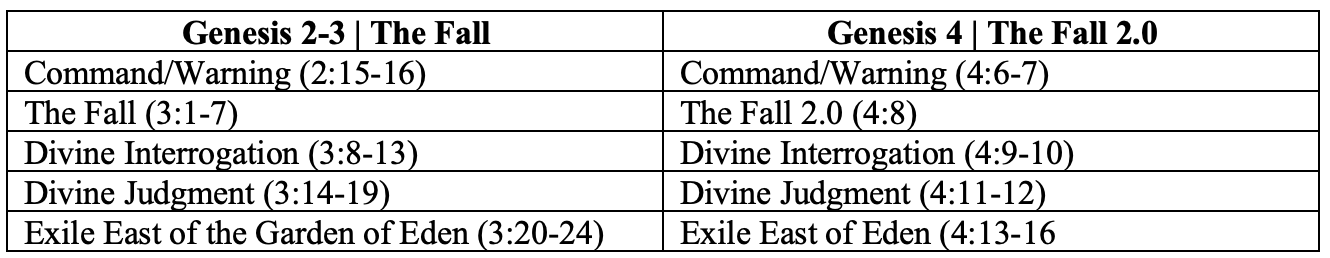

Furthermore, when the connections between Genesis 3 and Genesis 4 are recognized, the offerings can be seen to serve a similar function to the presence of the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden of Eden. At a literary level, both of these narratives include features that provide the necessary elements for conflict/complication. Just as a thorough exploration of the two trees may be valuable, an overemphasis on these elements fails to rightly locate their narrative function.

When Genesis 4 is read in light of Genesis 2-3, Cain’s offering is hardly the failure in view. It is Cain’s murder of Abel that parallels the transgression of both the man and the woman. Yahweh’s rejection of Cain’s offering merely presents the conditions for conflict/complication.

Relevant Statements in the Old Testament

Throughout the Old Testament, the Law and the Prophets emphasize the need for a circumcised heart (e.g., Deut 10:12-17). In sequential narratives, Yahweh makes clear that he desires obedience rather than sacrifice (1 Sam 15:22) and that, while humans look on outward appearances, he looks on the heart (1 Sam 16:7). From these statements in the Old Testament (and there are many more of them), we can conclude that while we may want to connect Yahweh’s rejection of Cain’s offering to something about the external materials, it is more likely a matter of the heart. Throughout Israel’s scriptures, we learn that the offering does not make a person acceptable to God. Rather, it is a person’s heart that makes the offering acceptable to God.

Many Old Testament texts should inform our reading of the Cain and Abel narrative, but I’m especially interested in two: Micah 6:7-8 and Hosea 6:5-9. I’m inclined to think that both contain allusions to Genesis 1-4. Although neither text directly references the Cain and Abel narrative, both address the issue of external offerings in contrast to what Yahweh truly desires: faithful love, not sacrifice, and the knowledge of God, rather than burnt offerings (Hos 6:6). Both of these texts emphasize the significance of faithful love for God in contrast to elaborate sacrifice.

When we read the Cain and Abel narrative in light of these (and other Old Testament) texts, it becomes clear that what God really wanted from Cain was not a revision to his offering, but an altogether different disposition of his heart.

New Testament Interactions with the Cain & Abel Narrative

The two New Testament texts that are most relevant to the discussion are Hebrews 11:4 and 1 John 3:11-12.

The author of Hebrews asserts that “By faith Abel offered a better sacrifice than Cain did” (Heb 11:4). This phrasing could mean that Abel offered a better sacrifice in terms of external quality (e.g., firstborn of his flock versus Cain’s produce). From this perspective, the idea is that Abel had the kind of faith that motivated him to offer the best of his flock, while Cain lacked that same kind of faith and therefore offered less than the best of his produce.4

It seems better to shift our attention away from the external quality of Abel’s offering to the internal heart posture of his heart. The author goes on to say that it was Abel’s faith that was met with God’s approval. It was his faith that made him approved as a righteous man. It seems to me that because Abel’s faith was counted as righteousness, his offering was accepted. His offering was better, not in terms of external material or quality, but because it came from a heart of faith.

The author of Hebrews emphasizes the positive example of Abel. In contrast, John emphasizes Cain’s negative example. He warns that we should not be like Cain, “who was of the evil one and murdered his brother” (1 John 3:12). Although John emphasizes that Cain’s deeds were evil, his greater concern in this passage is the love command. Underneath Cain’s external actions was a heart that failed to love.

John regularly recalls the beginning narratives of Genesis. Throughout, he introduces the love command as a command that is from the beginning. I take this to be a reference to Genesis 1-4. Although there is no direct love command in these narratives, they are all about love for God. In Genesis 3, the man and the woman fail to love God completely. In Genesis 4, Cain fails to love others sacrificially. John reads these two narratives as counterexamples of love for God and love for others.

The allusions to these two Genesis narratives continue in John’s presentation of Cain as the metaphorical seed of the serpent. He is “of the evil one,” which I take to be a statement of family relationship. Immediately before his reference to Cain, John says that the children of the devil and the children of God are identified based on whether they love others (and presumably God). It is when Cain murdered his brother rather than when he presented his offering that he proved himself to be the serpent’s offspring. In John’s view, it is Cain’s failure to love that is the real issue in the narrative.

The author of Hebrews emphasizes Abel’s faith and implies that Cain lacked faith. For that reason, Abel was counted as righteous, but Cain was not. Similarly, Cain is identified as the figurative offspring of the serpent because his heart lacked love for others. In both instances, the real issue was not the content or quality of an external sacrifice, but the internal disposition of the heart.

Conclusion

I’m convinced that the real issue with Cain’s offering was an issue with his heart. Unlike Abel and Abraham, Cain related to God without faith. For that reason, Cain could not be counted as righteous. The flow of the narrative, combined with the emphasis of the Old Testament texts cited above and the way that the New Testament authors utilize the Cain and Abel narrative, draws attention away from the external factors of Cain’s offering to the internal disposition of his heart. So what did God really want? He wanted Cain’s heart.

For example, N. T. Wright adopts an approach to narrative analysis proposed by A. J. Griemas and revised by Vladimir Propp that emphasizes chronological sequences and the relationship between sender, object, agent, receiver, helper, and opponent (The New Testament and the People of God [Fortress Press: Minneapolis, 1992], 69-80).

This approach is modeled by Todd L. Patterson in The Plot-structure of Genesis: ‘Will the Righteous Seed Survive?’ in the Muthos-logical Movement from Complication to Dénouement (Boston: Brill, 2018), 7.

This interpretation is common and is well-represented by Jim Hamilton in his sermon on Cain and Abel at Kenwood Baptist Church: https://kenwoodbaptistchurch.com/sermons/we-should-not-be-like-cain/.